How Women's Equality Changed Fragrance

But few movements in history have had as much of an impact on scent evolution as feminism.

It was the launch of Tabac Blond by Caron in 1919 that blew the delicate floral perfumes out of the water and marked a feminist revolution in the history of fragrance. Tabac Blond, with its sweet aroma of Virginia tobacco, had been conceived for men until Caron’s female artistic director, Felicie Wanpouille, realised it was the perfect scent for the rebellious, bobbed women emerging from the ashes of World War One.

“Liberation as a result of the suffrage movement meant women no longer wished to smell of flowers,” explains perfumer and scent historian Roja Dove. Why would they? When men were conscripted in 1914, these women took on their traditionally masculine jobs.

“Corsets and updos were no longer viable; these women wore trousers, worked hard, earned money and enjoyed a drink and a cigarette at the end of the day,” explains Diane Atkinson, suffragette historian and author of Rise Up Women! The Remarkable Lives Of The Suffragettes.

When men were conscripted, women took on traditionally masculine jobs: the Women’s Royal Air Force (WRAF) pictured in Narborough, Leicestershire, in 1919

By 1917, Coty had created what was arguably the earliest olfactive reaction to this shift in perceptions of femininity with Chypré, a scent that moved away from the heavy floral fragrances of the early Edwardian era by including oakmoss, musks and bergamot, which would have been considered masculine notes at the time. Chypré’s spirit fitted with what Atkinson describes as “the fresh-looking, more androgynous female” who came to replace traditional Edwardian ideals of femininity.

“Floral fragrances began to be replaced with new abstract, ‘louder’ perfumes crafted with tobacco, woods and leather,” explains Holly Dugan, author of The Ephemeral History Of Perfume: Scent And Sense In Early Modern England. “These perfumes reflected women’s shifting pursuits of pleasure, including smoking.”

Yet, no scent captured this better than Tabac Blond. “The scent had an audacity to it: bold, uncompromising and unprecedented, like the world it so perfectly encapsulated,” says Dove.

It was considered so shocking – certainly not the thing to be worn by ‘nice girls’ – that it gained huge popularity among the most provocative women of the era and paved the way for decades of scents that finally reflected the full experience of women – be that passion, strength, politics or sex.

Fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli, who created the iconic Shocking perfume

That pattern continued past the liberation of suffrage and post-war life. The interwar period – a progressive time in which women first entered UK Parliament – peaked, olfactively speaking, with the launch of Elsa Schiaparelli’s Shocking in 1937.

“To call Shocking sensual would be an understatement,” says Dove. “It was outright sexual.”

Civet, musk, ambergris and honey in the fragrance’s base gave Shocking an animalistic, predatory quality. It was sisters doing it for themselves, wrapped up in a voluptuous bottle with a bawdy ad campaign. This was female sexual emancipation bottled, and a big success.

The sexual liberation that resulted from historic legislation in the Sixties permitting women to legally take the contraceptive pill and have abortions, came to fruition in the Seventies and was encapsulated in Charlie, the iconic 1973 fragrance by Revlon.

Trouser-wearing, money-earning and vital, Charlie grabbed life by the balls. The campaign was groundbreaking in its choice of Naomi Sims, the first African-American model to star in a cosmetics commercial. The scent was a clash of zingy florals and testosterone-y vetiver, musk, oak moss and wood, which came in a slick, non-fussy (and certainly non-girlie) bottle. The Charlie girl was not to be trifled with.

Naomi Sims became the first African-American model to star in a cosmetics commercial when she was made the face of Revlon’s Charlie fragrance

A global recession spurred the next shake up of gender politics. “The Nineties began with the denunciation of conspicuous consumerism after the 1987 stock market crash,” says Dove. “It became the decade of global social conscience.”

This spawned the gap-year-loving, neohippie generation. The rise of Britpop and grunge, meanwhile, cemented an alternative, gender-sharing aesthetic – women were just as likely to be in a parka, hoodie or DMs as men, while androgynous models Kate Moss and Stella Tennant were ubiquitous.

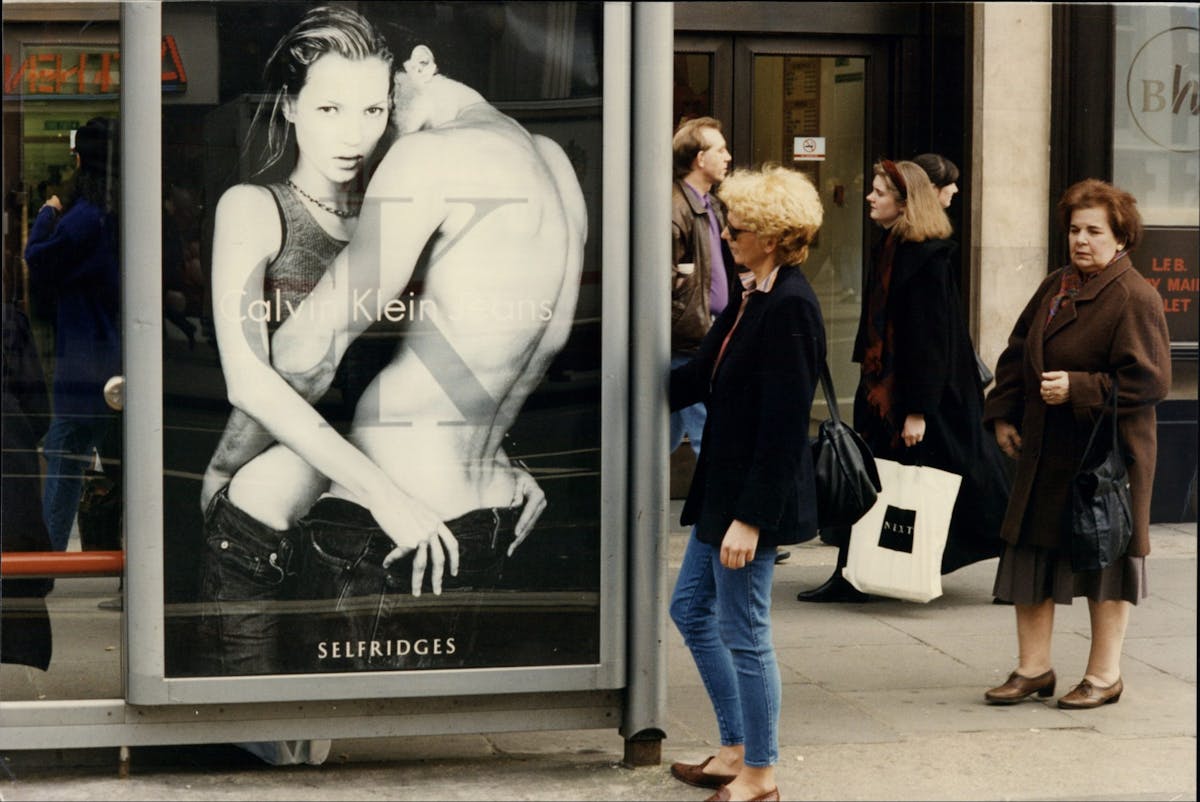

The fragrance world’s response to this was game-changing. “The most impactful feminist fragrance of the 20th century was CK One,” says perfumer Azzi Glasser. “It was blatantly marketed as unisex, which had never really been done before. The message was that boys and girls were wearing the same fragrance, and that was not only acceptable, but cool.”

In perfume terms, CK One promoted gender equality with its ultra-fresh scent combining traditional cologne notes with feather-light florals. Housed in almost utilitarian ‘don’t-label-me’ packaging, buyers had the choice of dousing or spraying the fragrance.

Kate Moss in an advertisement for Calvin Klein, 1994

Today, we’re reaping the effects of global marches to incite change – institutional harassment is being exposed and condemned; unequal pay is under examination. Qualities of transparency, action, women supporting women, equality and gender fluidity have trickled down into perfume bottles the world over.

Best of all, world events are no longer simply shaping the fragrances we wear, but improving the business practices and ethics of those who create them.

“Every consumer product has a place in the feminist movement because there are so many industries in which female workers could be treated more fairly,” explains Amy Christiansen Si-Ahmed, founder of Sana Jardin, a fragrance house that supports female entrepreneurship in the communities providing its ingredients. Their scent Revolution de la Fleur – with energising ylang-ylang – was even created as an ode to the women’s movement of 2017.

Feminista, meanwhile, is one big no nonsense activist of a brand. Set up to fund and promote equal rights campaigns, it’s “the first political perfume in the world dedicated to feminism”, according to co-founder Ulrike Hager.

With each sale, the brand contributes to causes such as Lady Parts Justice, which campaigns for reproductive rights. The scent’s clash of violet, leather, pink pepper and cedar is, in the words of creator Geza Schön, “suitable for all pronouns”.

Two women smell perfume by Comme des Garçons at the ‘Perfume: A Sensory Journey through Contemporary Scent’ exhibition in London, June 2017

This inclusive approach is key to the direction in which feminist fragrances are moving – promoting equality for all and reflecting the wider trend for eschewing gender labels.

“The global mindset is shifting towards an outlook on gender that rejects rigid male/female categorisations,” explains Victoria Buchanan, strategic researcher at The Future Laboratory. In olfactive terms, ‘gender fluid’ or ‘gender neutral’ are the biggest movements the industry has seen for years, with research showing global unisex fragrance launches grew from 9.5% in 2015 to 11.9% in 2016, and non-genderspecific brands reporting double-digit growth.

The established houses such as Diptyque, Tom Ford, Le Labo, Jo Malone, Byredo and Comme des Garçons, have been flying the flag for gender-neutral scents for years. Many are now taking it one step further by combining polarising notes once perceived as very male (moss, ferns) or female (white flowers) in a sort of ‘omnisex’ approach.

“Just like in 1918, feminism has once again led us into a second golden age of perfumery,” says Michael Donovan, owner of independent brand Roullier White. “A refusal by contemporary women to be told what is or is not gender appropriate has contributed to the explosion of the artisan perfume market, where it is now rare for a brand to define a fragrance by gender. It is increasingly left to the individual to decide what excites and suits them personally, and to dare to be themselves.”

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more delivered straight to your inbox

_____________

References:

https://www.stylist.co.uk/beauty/perfume-feminism-history-womens-suffrage/188087

Photo by Jen Theodore on Unsplash

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Bosnia & Herzegovina

Bosnia & Herzegovina

Bulgaria

Bulgaria

Canada

Canada

Croatia

Croatia

Cyprus

Cyprus

Czechia

Czechia

Denmark

Denmark

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Germany

Germany

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Iceland

Iceland

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Latvia

Latvia

Lithuania

Lithuania

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Malta

Malta

Mexico

Mexico

Monaco

Monaco

Netherlands

Netherlands

Norway

Norway

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Rest of the World

Rest of the World

Romania

Romania

Serbia

Serbia

Slovakia

Slovakia

Slovenia

Slovenia

Spain

Spain

Switzerland

Switzerland

Sweden

Sweden

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

United States

United States